The 2020 presidential election will be the first in 40 years to take place without a federal judge requiring the Republican National Committee to seek approval in advance for any “ballot security” operations at the polls. In 2018, a federal judge allowed the consent decree to expire, ruling that the plaintiffs had no proof of recent violations by Republicans. The consent decree, by this logic, was not needed, because it worked.

The order had its origins in the New Jersey gubernatorial election of 1981. According to the district court’s opinion in Democratic National Committee v. Republican National Committee , the RNC allegedly tried to intimidate voters by hiring off-duty law-enforcement officers as members of a “National Ballot Security Task Force,” some of them armed and carrying two-way radios. According to the plaintiffs, they stopped and questioned voters in minority neighborhoods, blocked voters from entering the polls, forcibly restrained poll workers, challenged people’s eligibility to vote, warned of criminal charges for casting an illegal ballot, and generally did their best to frighten voters away from the polls. The power of these methods relied on well-founded fears among people of color about contact with police.

This year, with a judge no longer watching, the Republicans are recruiting 50,000 volunteers in 15 contested states to monitor polling places and challenge voters they deem suspicious-looking. Trump called in to Fox News on August 20 to tell Sean Hannity, “We’re going to have sheriffs and we’re going to have law enforcement and we’re going to have, hopefully, U.S. attorneys” to keep close watch on the polls. For the first time in decades, according to Clark, Republicans are free to combat voter fraud in “places that are run by Democrats.”

Voter fraud is a fictitious threat to the outcome of elections, a pretext that Republicans use to thwart or discard the ballots of likely opponents. An authoritative report by the Brennan Center for Justice, a nonpartisan think tank, calculated the rate of voter fraud in three elections at between 0.0003 percent and 0.0025 percent. Another investigation, from Justin Levitt at Loyola Law School, turned up 31 credible allegations of voter impersonation out of more than 1 billion votes cast in the United States from 2000 to 2014. Judges in voting-rights cases have made comparable findings of fact.

Nonetheless, Republicans and their allies have litigated scores of cases in the name of preventing fraud in this year’s election. State by state, they have sought—with some success—to purge voter rolls, tighten rules on provisional votes, uphold voter-identification requirements, ban the use of ballot drop boxes, reduce eligibility to vote by mail, discard mail-in ballots with technical flaws, and outlaw the counting of ballots that are postmarked by Election Day but arrive afterward. The intent and effect is to throw away votes in large numbers.

These legal maneuvers are drawn from an old Republican playbook. What’s different during this cycle, aside from the ferocity of the efforts, is the focus on voting by mail. The president has mounted a relentless assault on postal balloting at the exact moment when the coronavirus pandemic is driving tens of millions of voters to embrace it.

This year’s presidential election will see voting by mail on a scale unlike any before—some states are anticipating a tenfold increase in postal balloting. A 50-state survey by The Washington Post found that 198 million eligible voters, or at least 84 percent, will have the option to vote by mail.

Trump has denounced mail-in voting often and urgently, airing fantastical nightmares. One day he tweeted, “mail-in voting will lead to massive fraud and abuse. it will also lead to the end of our great republican party. we can never let this tragedy befall our nation.” Another day he pointed to an imaginary—and easily debunked—scenario of forgery from abroad: “rigged 2020 election: millions of mail-in ballots will be printed by foreign countries, and others. it will be the scandal of our times!”

By late summer Trump was declaiming against mail-in voting an average of nearly four times a day—a pace he had reserved in the past for existential dangers such as impeachment and the Mueller investigation: “Very dangerous for our country.” “A catastrophe.” “The greatest rigged election in history.”

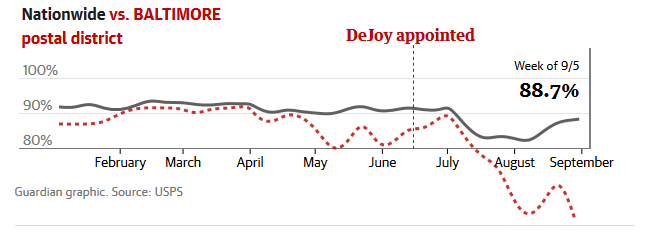

Summer also brought reports that the U.S. Postal Service, the government’s most popular agency, was besieged from within by Louis DeJoy, Trump’s new postmaster general and a major Republican donor. Service cuts, upper-management restructuring, and chaotic operational changes were producing long delays. At one sorting facility, the Los Angeles Times reported, “workers fell so far behind processing packages that by early August, gnats and rodents were swarming around containers of rotted fruit and meat, and baby chicks were dead inside their boxes.”

In the name of efficiency, the Postal Service began decommissioning 10 percent of its mail-sorting machines. Then came word that the service would no longer treat ballots as first-class mail unless some states nearly tripled the postage they paid, from 20 to 55 cents an envelope. DeJoy denied any intent to slow down voting by mail, and the Postal Service withdrew the plan under fire from critics.

If there were doubts about where Trump stood on these changes, he resolved them at an August 12 news conference. Democrats were negotiating for a $25 billion increase in postal funding and an additional $3.6 billion in election assistance to states. “They don’t have the money to do the universal mail-in voting. So therefore, they can’t do it, I guess,” Trump said. “It’s very simple. How are they going to do it if they don’t have the money to do it?”

What are we to make of all this?

In part, Trump’s hostility to voting by mail is a reflection of his belief that more voting is bad for him in general. Democrats, he said on Fox & Friends at the end of March, want “levels of voting that, if you ever agreed to it, you’d never have a Republican elected in this country again.”

Some Republicans see Trump’s vendetta as self-defeating. “It to me appears entirely irrational,” Jeff Timmer, a former executive director of the Michigan Republican Party, told me. “The Trump campaign and RNC and by fiat their state party organizations are engaging in suppressing their own voter turnout,” including Republican seniors who have voted by mail for years.

But Trump’s crusade against voting by mail is a strategically sound expression of his plan for the Interregnum. The president is not actually trying to prevent mail-in balloting altogether, which he has no means to do. He is discrediting the practice and starving it of resources, signaling his supporters to vote in person, and preparing the ground for post–Election Night plans to contest the results. It is the strategy of a man who expects to be outvoted and means to hobble the count.

Voting by mail does not favor either party “during normal times,” according to a team of researchers at Stanford, but that phrase does a lot of work. Their findings, which were published in June, did not take into account a president whose words alone could produce a partisan skew. Trump’s systematic predictions of fraud appear to have had a powerful effect on Republican voting intentions. In Georgia, for example, a Monmouth University poll in late July found that 60 percent of Democrats but only 28 percent of Republicans were likely to vote by mail. In the battleground states of Pennsylvania and North Carolina, hundreds of thousands more Democrats than Republicans have requested mail-in ballots.

Trump, in other words, has created a proxy to distinguish friend from foe. Republican lawyers around the country will find this useful when litigating the count. Playing by the numbers, they can treat ballots cast by mail as hostile, just as they do ballots cast in person by urban and college-town voters. Those are the ballots they will contest.